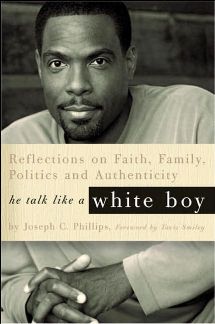

A Review of Joseph C. Phillips'' Reflections on Faith, Family, Politics, and Authenticity

"I have grown tired of hearing people badmouth America. I love my country and claim it as my own because I believe America is good. And to those who would question my allegiance to a nation that once enslaved folk who looked like me, I answer that I proclaim my Americanness precisely because my people are on the soil...

I’ve grown tired of the one-dimensional portrayal of black life in our cultural discourse- the pessimism, nihilism, and hedonism. I have grown frustrated by the limits imposed on black individuality by white liberals, and I have grown impatient with the limits that are just as often imposed by the black community.

As quiet as it’s kept, black people like me exist, and I grow more convinced every day that more and more black people share my thoughts on a great many subjects.”

- Excerpted from the Introduction

By the time Joseph Phillips added a syndicated columnist to his resume, he was already a famous actor. Perhaps best known as Lisa Bonet’s husband on The Cosby Show, the handsome thespian is still making movies and guest-starring in a variety of TV series.

But now Joseph has also become a rather highly-regarded social commentator, with his articles appearing in Newsweek, Essence, USA Today and the LA Daily News, to name a few publications. Because so many of the glowing blurbs on the cover of He Talk Like a White Boy came from noted African-American conservatives such as Shelby Steele, John McWhorter, Larry Elder, Ward Connerly and former Republican Congressman J.C. Watts, I braced myself for a book likely to parrot the black neo-con party line.

And though he does devote considerable space to praising Presidents Reagan, Bush I and Bush II while criticizing Carter and absolutely trashing Clinton (“a lying snake who harboured genuine contempt for the people he was sworn to serve”), this critic must admit that I was otherwise pleasantly surprised, overall, by this intimate and insightful collection of essays. Besides those brief, if aggravating, interludes given to playing partisan politics, this engaging compilation of observations and personal anecdotes about being black in America actually borders on the brilliant.

Unfortunately, it is still very difficult for a leftist like me to stomach Phillips’ going overboard to extol the virtues of Bush II as “a man of vision, conviction and faith” and of Reagan, who I remember repeatedly referring to Nelson Mandela as a terrorist while supporting South Africa’s apartheid regime. Such infuriating asides make one wonder whether this brother only talks like a white boy or maybe might even think like one.

Speaking of “talking white,” the book takes its title from an incident that occurred in a classroom back when Joseph was in junior high school. It was the first time his absence of a ghetto accent was pointed out and made an issue. He recounts how he felt hurt that his African-American credentials had been questioned on the basis of how he spoke. Yet, he simultaneously asserts that rather than being scarred by the experience, “The man I am today had its genesis in that moment.”

Phillips is at his best at such transformational moments when reflecting in some fashion upon his own blessed life, which began with his being raised relatively privileged in the Denver suburbs and led to his studying theatre at NYU, which enabled him to embark on a showbiz career which has led him to Los Angeles Hollywood where the very happily-married father of three sons makes a home in Hollywood with his wife, Nicole, and their three sons, Connor, Ellis and Samuel.

I frequently found myself wincing with the pain of recognition when he reminisced about perhaps not measuring up to subtle social pressures to “party” or “play ball.” Frankly, as long as he avoids the subject of politics, I didn’t find myself disagreeing with him very often.

The central message of this timely memoir is the Cosby-esque notion that the time has arrived for black people to stop narrowly identifying with the assorted negative images propagated by popular culture via gangsta rap, such as black-on-black crime, misogyny, drugs and murder. Phillips can be quite eloquent and entertaining when deconstructing the harm of such self-destructive behaviours and pointing the way to viable alternatives.

Nonetheless, all the pandering to the right wing in other chapters implies that anyone who is polite, well-dressed and speaks proper English also ought to agree automatically with his dubious political leanings. And I just ain’t ready to drink that Kool-Aid yet.