Something’s been bothering me about the movie Borat. I could not identify what it was exactly, but I knew I had to try to dig it out of me. It was only recently, when watching Bamboozled for the fifth time that Spike Lee’s words at Roy Thomson Hall last year came back to me. “Think about it,” he said, referring to a pilot for a TV show he was presenting. “They wanted to make a sitcom about Slavery! Would anybody think about making a sitcom about the Holocaust?”

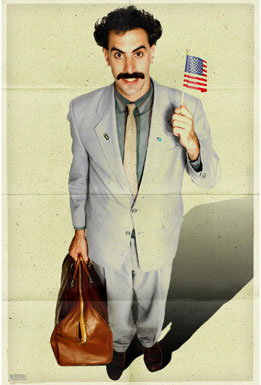

Borat, for those of you who have been stuck in a village in… Kazakhstan for the past few years, is a fake documentary story about a fake Kazakh reporter who travels the U.S., meeting people and engaging them in discussions about their customs, their feelings about other races as a way of supposedly getting the cultural pulse of Americans; Borat: Cultural Learnings of America for Make Benefit Glorious Nation of Kazakhstan is the full title of the movie after all.

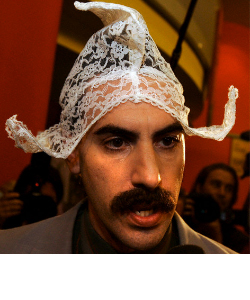

The main character of Borat is played by Sacha Baron Cohen, a Cambridge-educated British comedian who was first introduced to North American audiences through his critically acclaimed TV show Da Ali G Show. In the TV show, as in this movie, and fully in character either as Ali G (a loudmouth fake gangsta rapper) or as Borat, Cohen interviews various famous and notable people. Some of his past victims include British soccer star David Beckham, Donald Trump, Shaquille O’Neal and former U.N. Secretary-General Boutros Boutros Ghali. Most of Cohen’s interviewees are unaware of the joke being played on them. This, therefore, allows him to get candid answers to very personal and politically incorrect questions.

The movie Borat, like Da Ali G Show before it, is viewed as satire—nothing to be taken too seriously or harshly analyzed. Indeed, many of the people I talked to who watched the film saw it that way, too: mindless fun. Satire is usually meant to poke fun at a set of ideas or belief systems. It ridicules something that its author wishes to criticize, demonize, or plainly present as irrational and unacceptable.

In the Ali G series, Baron Cohen ridiculed his interviewees, the assumptions they held about gangsta rappers, Rap Music in general and the racial and age group that produced it. In Borat, the target of his ridicule at first glance appears to be the beliefs that he views as permeating the American mainstream and the American people, presented as self-interested, intellectually abject and geographically illiterate.

Anti-Semitism is at the top of Sacha Baron Cohen’s list of items to ridicule in Borat. In one of the most talked-about scenes in the movie, Borat interviews a ranch owner who says he would have “no problem” running a ranch where people hunt for “deer and Jews.” In a promotional clip for the movie, still in character, Cohen throws out an invitation to his “idol” “Mel Gibsons” to see his movie. Borat himself is blatantly anti-Semitic, which makes it easy to draw in equally bigoted interviewees and elicit commentary they would probably not provide to a mainstream American reporter.

Racism is the other target of Sacha Cohen’s satire. Our friendly Kazakh reporter befriends many African-Americans in the film (perhaps as a way of shining a light on their predicament), including the prostitute Luenell, whom he ends up marrying. He also engages drunken fraternity boys who confide to him that they would not have an issue with the return of slavery in America. And perhaps just to show that such feelings are not confined to the lower echelons of American society, he attends an upscale dinner in the South on the street called … Secession Drive.

No sacred symbols are safe in this film. Even the American national anthem, the Star-Spangled Banner, gets a serious beating as Borat sings a distorted version of it as the Kazakhstan national anthem.

Perhaps to reinforce his point on the hopelessness of the average American’s knowledge of the rest of the world, throughout his travels in the U.S., Borat speaks in Hebrew when pretending to speak his native Kazakh language. The villagers in the opening sequence, where Borat introduces his village to us, speak Romanian. Kazakhstan is not present in the film; it is only mentioned as a place, a foreign place far away, different and weird in the eyes of the average American Borat meets along the way.

|

So, on the surface, one would say that the film Borat reached its goal; if the goal beyond the laughs was to highlight the stupidity of anti-Semitism and the vile nature of racism and encourage us to toss the remote controls and visit a few public libraries. However, one could also argue that it did and is doing much more than that. You see every satire, especially Sacha Cohen’s kind, requires a subject to carry its message. And willingly or not, the subject can easily become a victim of his/her own comedy. In the process of poking fun at hatred, Sacha Baron Cohen ends up poking fun at Borat, the fake Kazakh reporter too. Kazakhstan (and, by default, all those obscure faraway Third World countries) is presented as an uncivilized, savage country where Borat maintains a cow in his bedroom. His sister, he tells us gleefully is “the #4 prostitute in Kazakhstan ” and his village has a “Village Rapist”. The geographically-illiterate American that Cohen shows us in the film can only accept this presentation as reality and use it as additional ammunition for his hatred and disenfranchisement of “others”. |

Even when he donned the Ali G uniform, Sacha Baron Cohen never provided a counterview of the ignorant, in-your-face gangsta rapper who maligned his interviewees. This left the public with only the stereotypes that already pervade the mainstream TV shows, movies and magazines. With Borat, the same scenario reproduces itself. Nobody gets to present a more appropriate picture of Kazakhstan, its people, its landscape, and its history. The public is merely left with the stereotypes they brought into the movie theatre and actually leaves with more of them. Borat seemingly mocks everything around him but provides no counterpoints.

So, back to Spike Lee. The strength of his movie Bamboozled lies in the fact that his characters Manray and Womack eventually realize the long-term effect of their “black face” performance on their audience and on themselves and thereby acknowledge the limits of comedy. “No. You can’t make a sitcom about Slavery!” is the message their gesture sends us. Borat does not have such a moment.

In this post-September 11th age of quasi-accepted anti-Arab, anti-Muslim sentiment, when a commentator like Glen Beck on CNN Headline News can openly express his fear of a newly elected Muslim Congressman (see clip), simply because he prays to Allah instead of Jesus Christ, movies like Borat only add fuel to this anti-otherness fire. They contribute to demonize the “others”, those individuals relegated to the margins of what George W. Bush and his right-wing ilk like to call “Civilization”. Today it is Kazakhs, Arabs, Muslims or any inhabitant or native of the “stan” countries. Tomorrow, it may be Black people again or any other non-dominant ethnic group. Or maybe I am taking this silly movie a little too seriously?

In any case, empires need grand narratives, and artists usually provide them. Beware of your role in propagating these messages.