Each year, the Hot Docs documentary festival—the largest in North America—showcases over 200 engaging documentary films from Canadian and international storytellers for the enjoyment of more than 200,000 audience members in Toronto. However, following the announcement of the annual festival's postponement due to the COVID-19 pandemic, a sample of films from the 2020 Festival Selections are being made available for viewing this week on CBC.

The exclusive first-run feature documentaries will premiere this Thursday, April 30th, on the free CBC Gem streaming service and documentary Channel.

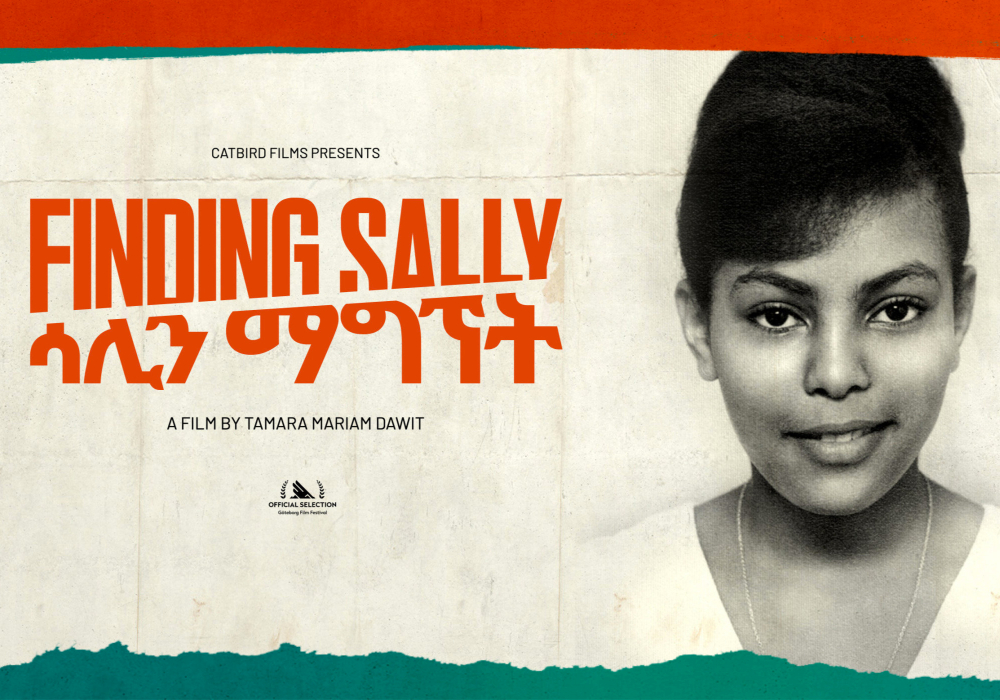

One of these "Hot Docs at Home on CBC" featured premieres is Finding Sally (2020, 78 min) by Ethiopian-Canadian filmmaker Tamara Mariam Dawit. Catch the world broadcast premiere on CBC & CBC Gem at 8:00 PM (8:30 NT), and on documentary Channel at 9:00 PM ET/10:00 PM PT.

The film captures the incredible story of Selamawit "Sally" Dawit, the filmmaker's late aunt she never knew. Sally, the daughter of an Ethiopian dignitary, moved to Ottawa with her sisters, brother (Tamara's father) and her parents in 1968. The upper-class family settled in well, and despite experiencing various forms of racism as one of the few black families around, Sally was a charismatic young woman with an active social life.

A bright student at Carleton University, the embassy brat had no shortage of friends and hopeful suitors. Sally seemed destined to continue living a life of privilege until a fateful summer trip back to her homeland of Ethiopia in 1973, from which she would never return, changed everything.

The revolution

"The thing that I really learned through the process of researching for this film and dissecting my family history was that my family talked a lot about Ethiopia and their stories and their memories of Ethiopia in the 1950s, 60s or 40s. And then, after 1974, it stopped, and it was like a black hole," as Tamara Dawit shared with me via a Zoom call from her current base in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

This watershed event in September 1974 was the overthrow of Emperor Haile Selassie from power in Ethiopia, who had ruled the country since 1930—ultimately setting off the end of the Solomonic dynasty.

The coup was led by the Derg, a Marxist-Leninist military junta officially known as the Provisional Military Government of Socialist Ethiopia, which went on to rule Ethiopia until 1987. As soon as the Derg gained power as a provisional government, they were challenged by various communist groups, including a significant youth movement, who felt Derg's leadership had abandoned their people-focused communist ideals.

A prominent opposing group challenging the Derg was the Ethiopian People's Revolutionary Party (EPRP). This is the group Sally joined when she returned to Ethiopia for a summer holiday in 1973. She fell in love with an EPRP rebel leader, Tselote Hizkias, and they were soon married in a small civil ceremony.

Together, they fought a guerrilla war against the Derg after being part of the original Marxist-Leninist coalition to overthrow Emperor Haile Selassie — a close acquaintance of her own father and the Head of State under whom her father was appointed as a diplomat to Canada.

Persecuted by the Derg, Sally and her comrades fled Addis Ababa and went underground — vanishing into the mountains of Northern Ethiopia. The bloody two-year period of the "Red Terror" from 1977 to 1978 was marked by widespread violence, torture and state-sponsored murder as the Derg sought to track down the "enemies of the state."

Some forty years later, Sally's niece Tamara embarked on a cinematic journey to trace back her mysterious journey in an effort to find answers and break the family's silence.

"I really realized that because a lot of painful and terrible things happened [during that time], that's why there weren't many happy memories to share after the revolution in the country," said Tamara. "It's easier to try and forget or suppress those memories and emotions. It almost just becomes common practice. I think even today, Ethiopia has a huge cultural hangover from communism. Those shackles can take a long time to sort of throw down and break free from."

The ties that bind

Born in Canada in 1980 to a Canadian mother, Tamara grew up with her mother but kept seeing her Ethiopian father until around the age of 15. She also remained close to many members of her extended Ethiopian family throughout her life. After the revolution, most of her family stayed either in Canada or the US, as returning home wasn't ideal or safe. So, during the first twenty years of her life, most of Tamara's relatives had not yet moved back to Ethiopia and were thus more accessible to her.

"I was very much surrounded by my father's relatives and had a lot of information about Ethiopia," she shared. There was always a sense that it's very important to be Ethiopian and that it's essential to go back and help the country. This is something you have a lot of honour in."

"I was very much surrounded by my father's relatives and had a lot of information about Ethiopia," she shared. There was always a sense that it's very important to be Ethiopian and that it's essential to go back and help the country. This is something you have a lot of honour in."

Tamara first journeyed to Ethiopia as a twenty-year-old.

"That was a great time of exploration because, of course, I'd always been hearing about places and people and things to do with the country's history and the family's history. But it's also something different to come here and experience it for yourself," as Tamara described.

Since then, she's been going to Ethiopia regularly to work on projects through her production company, Gobez Media, and to visit family. "There are so many other stories from Ethiopia that need to be told, and they need to be told by Ethiopian writers/directors from an Ethiopian point of view. That means there's a need for more support as a producer here," she said.

"So a lot of the other work that I do in Ethiopia is producing other filmmakers here and helping them with capacity building, with the development of their projects, with accessing funding, and getting their films out to international markets."

When she started the production of Finding Sally, Tamara made a conscious decision to spend the majority of her time in Ethiopia for a while.

Being ingrained in the country and closer to family allowed Tamara to pursue her research into Sally. "It was a huge benefit to the project," she said.

A missing chapter in the family's history

Tamara had always wanted to work on a project about the Ethiopian Revolution and the Red Terror. But it was only after she learned about her late aunt's existence in her early thirties that the concept finally took form.

"I only found out about my aunt Sally ten years ago when, sort of by accident, I came across her photo and said: Who is this?" This was the catalyst that led Tamara to pursue the film project.

Tamara had always thought she had four aunts. Then, suddenly, she realized she had a fifth.

I was curious to find out from Tamara why she thought her aunts, grandmother or any other family member, had never mentioned anything to her about Sally's existence and what could have motivated the secrecy. Could it have been because they disagreed with Sally's political ideology, which put at risk both her own life and jeopardized the family's safety? Tamara says:

"Of course, there are members of my family who probably weren't 100% supportive of some of the things that Sally did in alignment with her ideology. But I think the driving force for not talking about her is really the same as so many Ethiopian families who lost relatives in the 70s and 80s or had relatives who were jailed, disappeared or who were tortured. It's because you were not allowed to talk about these people; that was also dangerous. So when there's a culture of fear connected to that, it makes you less likely to talk about it."

Who was the real Sally?

She believes Sally was likely torn and conflicted between preserving and protecting the family structure she grew up in and fighting for a better future for her country. By going underground and changing her name, Sally's family could only rely on second or third-hand information about her whereabouts.

By choosing a new life and identity, Sally would also be becoming another person. Tamara was very conscious of that. So it was also important for her to get the accounts of Sally's fellow rebel associates and not only to get a picture from her aunts.

"I think they're all giving me sort of a different version of Sally, and it's the version that they're most comfortable with remembering right now in the present day. ... How they decided to reflect on their past in relation to their sister or their daughter," as Tamara astutely remarks. "[I also needed to] track down Sally's comrades and her friends who were with her underground, so I could actually have much better information about what was driving her. There are the people who were with her when she was involved in, I guess, what you would call espionage or when she took up arms."

Tamara gave those accounts from the trenches a bit more weight because she recognized that people change. The Sally that her aunts knew when they were living in Ottawa, which they remember so fondly, may not be the same Sally who ultimately ended up fighting for her communist ideology.

The work of remembrance ahead

As Tamara points out, the story of her family and the silence surrounding the post-revolution period of the Red Terror and beyond is far from unique. Many Ethiopian families in the Great Toronto area, Canada, the United States, and the diaspora share similar stories.

"If it's not them, it's the elders in their family, and I think it's certainly a piece of baggage that many people in our community carry around: the grief and the trauma attached to what happened," said Tamara.

I have personal friends whose parents arrived in Canada in the early 1970s and were likewise compelled to stay overseas and raise their families away from their beloved homeland. I wondered how they would feel about the film and the fact that it reopens old wounds and deep-seated political divisions. Tamara shares some of her insights about reactions from the Ethiopian community following small screenings at a film festival in Sweden:

"I found that the older generation who [attended the screenings] was happy to have a film that covered a period that they went through that was important to them. It was an opportunity for reflection. The younger generation didn't necessarily know that much about what happened because there's often a culture of silence. If something's painful, then you don't talk about it. And that means your parents don't tell you, and your grandparents don't tell you, and then you don't know about it."

She ends with the following observation:

"So for me, I think for Ethiopians, regardless of your political ideology or affiliation, I want people to watch this film, and then the best thing that can happen is that there's a conversation, and we start to talk more actively about our history. [We need to] start [having] more of an intergenerational dialogue within our households and within the community about what happened in the past and how we can look at that and understand it so that we can go forward in a more beneficial, fruitful and peaceful fashion."